|

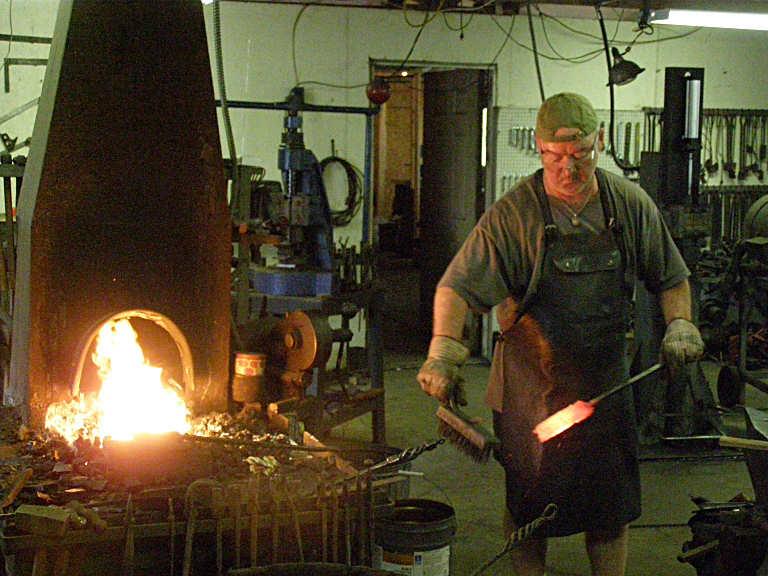

Damascus or Pattern Welded steel is an ancient process that traces it's

roots to India, thousands of years ago. The process as practiced today involves taking different

steels, and even pure nickel, and combining them together via a process

called forge welding. This is done by mating the metals carefully,

bringing them up to forging heat, using some anhydrous borax as flux,

and tapping them lightly with a hammer to set the welds. Once the welds

are solid, the monolithic piece of metal may be worked as desired. I

fold, twist, and continue to forge weld, in order to create the patterns

that I achieve in the finished blades.

I enjoy working with various materials,

including steel cable and chainsaw chain, in order to make some unusual

and interesting patterns. Since I do this by hand, it is very time

consuming and I don't make a lot of hand forged Damascus blades. It also

adds to the cost of the finished knives.

|

|

Creating

a Visible Temper Line (Hamon)

This is an ancient

technique, perfected by the Japanese during the height of the

Samurai era, for creating a differentially tempered blade. In making

a blade, you strive, during heat treating, to reach a balance

between hardness and toughness. The harder a blade is, the keener

edge it will take and hold. However, too hard and it will snap, or

at the very least, the edge will chip. Toughness is the opposite of

hardness, hence why a blade is tempered after achieving maximum

hardness, to make it more durable and not as prone to breakage. It's

not as critical in knives, due to the shorter length, but in swords

it was everything. The Japanese did this differential tempering via

packing refractory (heat resistant) clay onto the spine of the

blade, thereby preventing it from heating up as much as the edge,

and also slowing it's cooling in the quench. This is a careful,

time-consuming process, and works much better on simpler (less

alloyed) steels than it does on the newer, fancier cutlery steels. I

do this from time to time, in order to create the highest performing

blade I can. If you do it correctly, you end up with a blade that's

rock hard at the edge and dead soft at the spine. The different

grain structures created in this way will show a visible temper

line, or hamon.

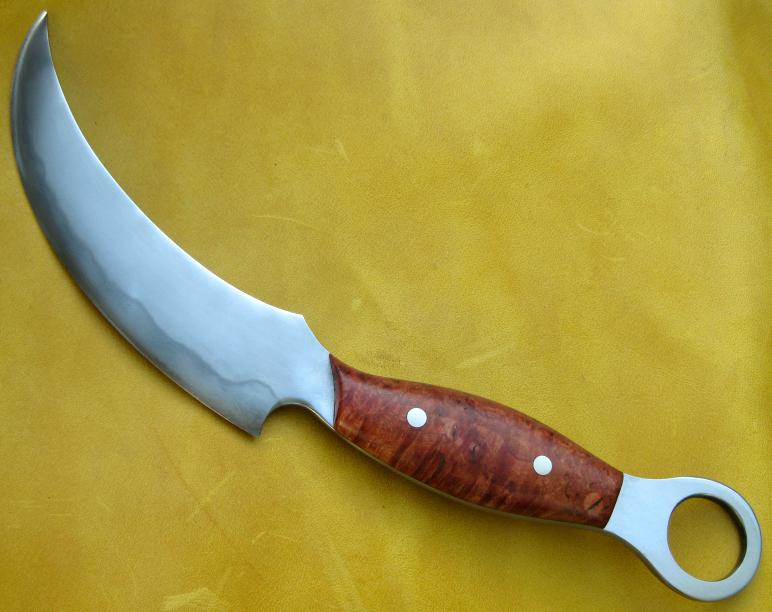

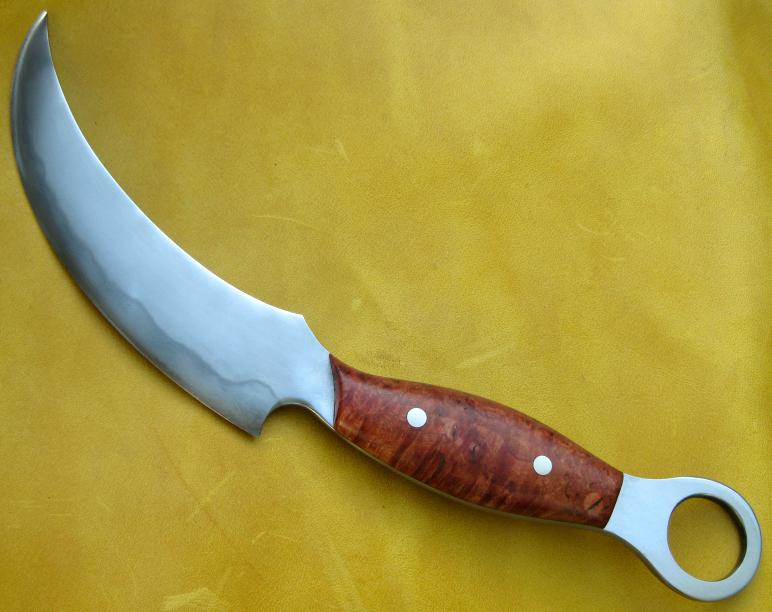

Here is an upswept

skinner blade, made of 1095, finish ground and hardened, showing the

clay on the spine. It was hardened in oil, hence the black coating

on the blade:

Another

pic, showing the entire blade:

Off with

the clay and clean it up. The pattern you see is surface

decarburization. This is a loss of carbon at the surface that

happens when the oxygen in the air combines with the steel during

the heating. Although it's pretty, it needs to be ground off to get

to the pure steel inside:

Decarb

ground off, with the blade etched to show the hamon:

Decarb

ground off, with the blade etched to show the hamon, another pic:

The

finished knife:

Rear

view. It worked well, the knife has a super hard edge and soft

spine, and I was able to get a nice hamon:

|

|

Wood Selection and

Stabilization

I've spent a lot of time sourcing the

finest possible selection of high quality exotic hardwoods from around

the world and have over 60 varieties in stock. I strive to only use

suppliers that sell sustainably harvested wood from non-endangered

species. Curing some of these woods is quite challenging. Snakewood, for

one, is one of the most difficult woods to cure correctly, to prevent

it's natural tendency to check (small cracks appearing). When a green

log is cut, to prevent any further curing you can coat the piece

entirely with paraffin wax, especially the ends. The end grain is where

most of the moisture escapes from as wood is curing. If you want to

achieve gentle, controlled curing, you coat the piece of fresh cut wood

with shellac, which is porous and will allow slow curing. Some woods are

extremely stable (Bubinga, for example), and may simply be cut and set

aside to age. Most all of the woods I have in stock, I have had here in

my shop for anywhere from 6 months to 2+ years, so they have all been

aged to ambient moisture content, and are ready to use.

Some woods are fully stable as is, and

some benefit from a process called stabilization. I've sourced a

proprietary chemical called Nelsonite, which was developed specifically

for the process of stabilizing wood. Pool cue manufacturers use it, as

does Scagel and other well known knifemakers. The chemical is carried in

a Xylene solvent and the wood block, once cut, is then soaked in the

Nelsonite for several days. The chemical makes it way into the wood,

displacing the natural moisture and saturating the fibers. After

soaking, the wood is air dried for several days to several weeks,

allowing the Xylene to evaporate, leaving the Nelsonite inside the wood

cells. What this does when the wood is used on a knife is to greatly

prevent the wood from either absorbing or releasing moisture as it

normally would, making it much more stable. Some woods do not need

stabilization and indeed will suffer from it. Ask me about stabilizing

woods, I can do that for you, should the wood need it, for a nominal

extra charge. One of the major benefits of this method of stabilization

is that the wood is left natural feeling, and will accept oil and wax

finishes readily, whereas some of the more common methods rely on

injected polymers, and leave the wood with a plastic like feeling and

finish. |